The Genki Ala Wai Project

Students, Teachers, and the Community Working Together

Response to Civil Beat Article: “Hawai‘i Loves ‘Genki Balls’ To Clean Water. New Studies Say They Don’t Work”

In response to the recent Civil Beat article, we would like to share our findings from the Ala Wai Canal. Our data show no negative impacts from Genki Balls. In fact, greater deployment of Genki Balls corresponds with larger reductions in sludge and lower Enterococci (fecal bacteria) counts, near the Convention Center, downstream of four Genki Ball deployment locations, where the Ala Wai flows out into the ocean. Full results are presented in Five Years of Water Quality Monitoring in the Ala Wai Canal, included here.

Number of colony forming units per 100 mililiters (cfu/100 mL)

The Genki Ala Wai Project is based on science, education, and community action. We monitor water quality using Department of Health parameters. Since our parent nonprofit, the Hawai‘i Exemplary State Foundation, is unfunded, this work relies entirely on donations and volunteer support. Over the past five years, we have invested more than $50,000 in third-party water quality testing. We are especially grateful to The Ritz-Carlton Residences, Waikīkī Beach, the Honolulu Festival Foundation, and Hawaiian Airlines for sponsoring two of our testing sites.

Regarding Hawai‘i Pacific University’s study referenced in the article, we first want to express our appreciation to the researchers. Their work is an important step in exploring the complex science of waterway restoration, and we value the time, effort, and expertise involved. We also thank Civil Beat for shining a spotlight on the Ala Wai Canal. Our technical advisor, Hiromichi Nago, collaborated with HPU’s research team during the early stages of their project. While the initial results did not align with what we had hoped, the report itself acknowledges that the study is incomplete. We look forward to HPU’s forthcoming work in Hāmākua Marsh, which we trust will provide a more comprehensive perspective.

We also offer professional comments on the study from Dr. Gustavo Pinoargote, President of EMRO USA, Inc.

In nature, microbes clean up waste, recycle nutrients, and help keep harmful bacteria in check. Effective Microorganisms (EM) technology supports these natural processes by strengthening beneficial microbes to maintain a balanced ecosystem. Genki Balls are one tool to help reduce sludge and pollution already in the canal. However, the true solution lies in addressing the sources of pollution upstream that continue to pollute the Ala Wai. Our forthcoming report will provide greater insight into these upstream impacts, and we invite the community to join us in tackling them together.

Mahalo for being part of this journey with us!

The Genki Ala Wai Project Team

Response to Hawai‘i Pacific University’s Study in Hāmākua Marsh

Dr. Gustavo Pinoargote

President, EMRO USA, Inc

Methodological Considerations in Microbial Detection

The study relied exclusively on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. While this is a standard approach for bacterial community profiling, it measures relative abundance rather than absolute activity, and does not account for other microbial groups such as fungi. The study also restricted “EM” to a short list of strains, and interpreted the absence of these strains in high relative abundance as a failure of EM. This overlooks EM’s intended ecological role, which is not to dominate or permanently colonize ecosystems, but rather to stimulate and rebalance native microbial communities by altering conditions such as pH, metabolite production, and redox states.

Ecological Interpretation of Relative Abundance

Interpreting EM effectiveness through dominance in sequencing data reflects a limited ecological view. Rare taxa can play critical functional roles, and microbial consortia such as EM are designed to act as catalysts: encouraging the growth of beneficial native microbes rather than displacing them. A decline in relative abundance after initial deployment is not necessarily failure, but instead aligns with EM’s intended role as a temporary stimulus that supports ecosystems in restoring their own balance.

Scale and Context of Experimental Design

Small-scale tank experiments can be informative as initial models of microbial interaction. However, they cannot fully capture the dynamics of natural wetland systems, which are shaped by hydrological flows, sediment chemistry, light cycles, plant interactions, and wildlife activity. These complexities are difficult to replicate in static tank conditions. For this reason, tank experiments are most appropriate as hypothesis-generating tools, and conclusions about field-scale effectiveness should be tempered with recognition of these limitations and the need for in-situ monitoring.

Framing and Language of Findings

Several conclusions in the paper were framed in absolute terms, such as stating that “no EM persisted” or that “Genki Balls are not a good deployment method,” without acknowledging detection limits or ecological complexity. Similarly, labeling entire genera as “pathogens” without supporting assays risks overgeneralization, as most genera (for example Bacillus, Streptomyces) contain both beneficial and opportunistic species. A more neutral framing would have been to describe observed shifts in community composition while noting uncertainties and methodological constraints.

Alignment Between Results and Conclusions

Interestingly, the study's own results showed that EM-associated microbes did appear transiently in both sediment and water, at times peaking at up to 17 percent. Rather than being evidence of failure, this pattern is consistent with EM's ecological function as a catalyst. Temporary establishment followed by decline reflects its role in promoting system resilience rather than persisting as a dominant population. Acknowledging this nuance would provide a more balanced interpretation of the findings.

Our Goal:

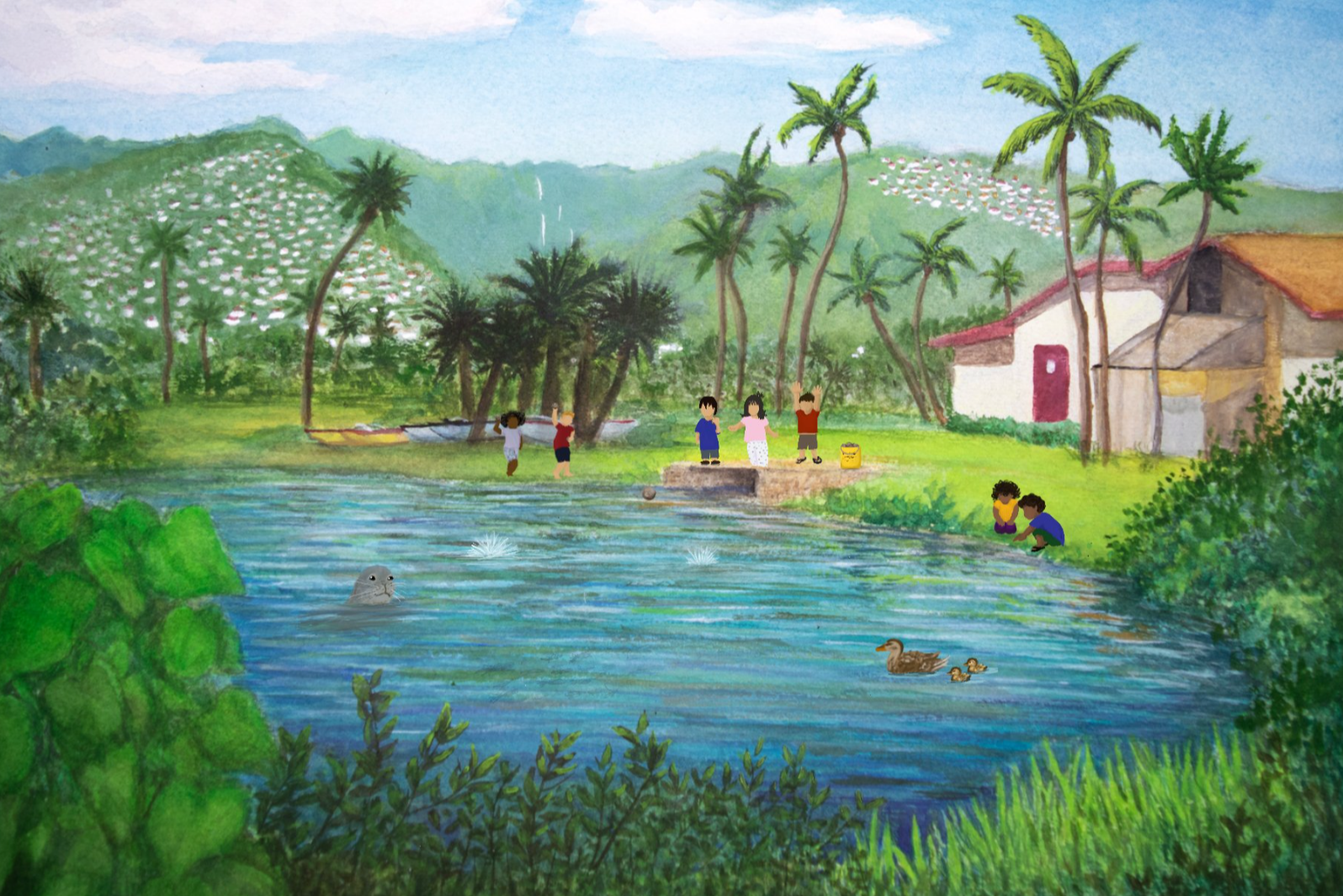

To deploy 300,000 Genki Balls and use Effective Microorganisms® (EM®) bioremediation technology to restore the Ala Wai Canal’s ecosystem by 2026, making it safe for fishing and swimming again. We hope that the success of this project will inspire the cleanup of other polluted waterways on the island.

Our Mission:

To empower students, teachers, and the community to work together to restore the ecosystem in the Ala Wai Canal.

Mahalo to our amazing partners!